Nov 12, 2012

Steelhead Fishing Tips - Winter

Now that it’s getting cooler and fish are a little less willing to chase flies way up in the water column, I thought I would pass on a few notes about cold-water steelhead presentation. Of course, steelhead are a mysterious lot and at times they shatter expectations. When the planets align they will certainly rise up to flies on floating lines. It happens, however if this is the way you choose to fish, then you must accept the fact that it might take you a very long time to touch a steelhead. As we move into winter, here’s a few things to bolster your chances while seeking these fish.

1. Seek lies in slower current

Cold water lowers fish metabolisms, lowers the frisky factor and makes them want to relax a little more. You won’t find them in fast water, unless there is a real obvious current break, like a boulder or a distinct depression in the river bottom. Spend most of your time fishing water that is moving at a slow walking pace or even a crawl. For most of your typical steelhead runs, this is the water that starts some distance downstream from the top- riffle, where the speed and turbulence dissipates into a more peaceful flow. This sweet spot may last all the way down into the tail-out and the lip of the next riffle depending on depth and current speed. If the tail-out isn’t moving too fast, then these areas make very happy homes. This however, is a typical scenario. If you just keep your eye on current speed and structure in the river bottom, you are on the right track. Look for differences in current speed and depth. Noticeable seam lines and darker shades in river color are key. But on average, be seeking out slower current than you would be if you were fishing in late spring – early fall.

2. Fish deeper

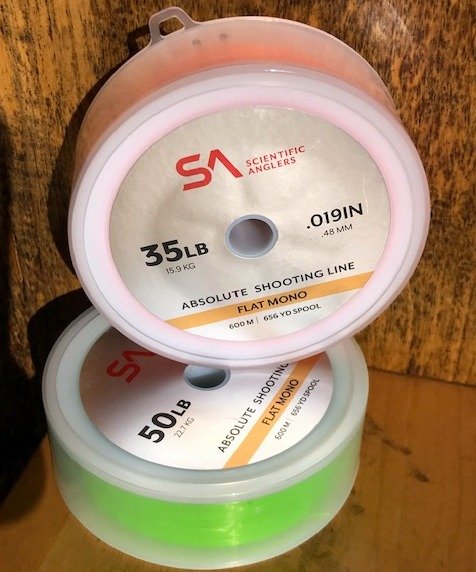

Sink tips, weighted flies, and tailored presentations will all help you bring your fly closer to the fish. Sink tip material like t-11 and t-14 (type 6 – type 8) affixed to Skagit Spey Lines are pretty typical for this time of year. However, the tip you choose really depends the water you are fishing. When the river is clear and cold, fish may hunker down deeper and tuck into little slots in the river. Essentially, they are looking for slow water that they also feel protected in. When this is the case, sink tips and careful presentations are key. Here is where casting angle, casting length as well as line management after the cast all come into play. Typically, all the following hold true: The farther upstream you cast -> the deeper your fly will get; The longer you cast -> the less you will be able to tailor depth; The size of your mend affects fly depth. Fishing in cold weather months demands that you take a harder look at the water and try to figure out where, exactly, these fish are hiding. Picture where they are and then try to fish your fly at depth and at the right speed where you think it matters most. This is key, because tips essentially shorten your presentation window. Your fly will lose speed and either be too shallow or too deep to be effective. There can be a lot of setup to get your fly at the right depth and angle and speed where these fish live.

Some notes about coldwater mending. If we want to get deep, we need to first remove tension off the fly so that it can sink. Unlike a basic floating line adjustment where we simply maneuver the fly line to adjust tracking angle, if we want to really achieve depth we must add slack after the line lands. Usually, this means an upstream mend and then a lowering of the rod tip. By lifting up and then giving back, we create a slack window. However, it is the giving back that is key. If you pull your line upstream but fail to give back, you have not added slack. Take and then give. We don’t particularly care about getting that fly swinging immediately. We want it to first sink to the desired depth and then come into a swing, at depth, where it counts. A typical casting angle in winter is 90 degree- or straight across the river, followed by a mend. If we want to get deeper, we can cast a little further upstream or increase the size of our mend – or both. By stepping down stream after our initial mend, we also give our fly more time to sink. Figuring this all out is up to you. If you are hooking bottom where the fish live, then bring your casting angle downstream, decrease the size of your mend – or both.

Please keep in mind that this is a typical cold/clear scenario. If water clarity is off-color, thereby providing cover for fish, then you want to pay careful attention to soft-water, in tight to shore. Even shallow tail-outs of only a foot in depth can hold fish if the water is colored up - so don’t go too heavy or too deep when this is the case. If we want our flies still swimming in tight to shore, we need to lighten up the tip, allow less time (slack) to sink, decrease over all casting length – or all of the above.

A note on fly choice: weighted flies have a huge effect on depth. Large lead-eyed flies will sink at a rate faster than most of your sink-tips. If you need to fish a deep slot, then increasing leader length off the tip will allow it to sink quicker – although this can be much harder to fling out there.

3. Fly Speed

Let’s keep on with the whole slower theme. On average, we want to slow down fly speed during winter months. Extend the amount of time the fly is hanging there tantalizing and trying to draw that fish into a duel. Of course we still want to subscribe to the whole thing about slowing down the fly in faster flows and speeding up in slower flows – but over-all, think about slowing it down a notch across the board during winter months. Much like tailoring depth, what you do with your fly line after the cast is paramount to influencing fly speed. By leading with our rod tip and staying in front of the fly, we encourage a faster swing. The current grips that line and creates a sort of downstream belly which acts to move that fly at a faster pace with a more broadside profile. The extent to which we lead the fly determines the speed. Not only that, the depth that we are fishing the fly, also has an influence on speed. Furthermore, the end of our swing tends to move slower than the beginning of our swing – usually. Many tried and true winter fly patterns are big – leaches, prawns and everything in between. When fishing these patterns it’s best to show off their figure a little. Give the fish that broadside view, you know, flaunt that big figure. So when we are swinging these flies, we do want a little downstream belly in our fly line. We do want to lead the fly just a bit, but finding just the right profile/speed is key. Add some profile, but fish the swing slowly and at depth. By sinking the fly, we also work to slow the fly down when it does come under tension. A fly at depth, can be lead (and its profile enhanced) without fishing it too fast. Increase depth -> slow the fly down. Furthermore, the less you lead the swing, the slower the swing. A straight line at depth will move the slowest. A line with a bow in it pointing towards your shoreline will move faster. Find the balance.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(

Atom

)

No comments :

Post a Comment